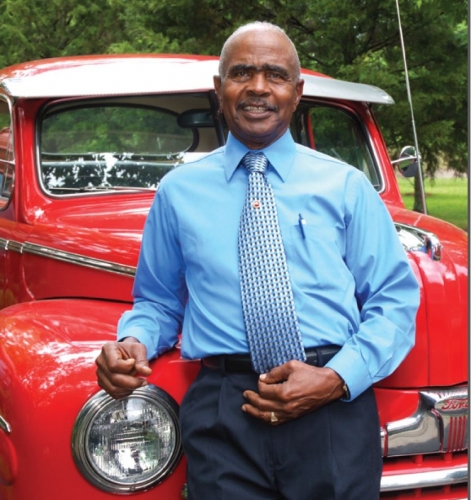

Jimmy Crudup

How a lab tech with no formal medical education became widely regarded as the finest surgery teacher at Michigan

To get to Forest, Mississippi, drive east out of Jackson about 35 miles, then north on Highway 35 past the massive, new Wal-Mart on the left. Turn east on Old U.S. 80, then north on Route 21, where a chicken - fallen from a truck bound for the local poultry processing plant - flaps, unsure, in the middle of the road. Just ahead, on the front steps of his tidy, brick home, waits Jimmy Crudup - a former truck driver who lives on the land where he was born in 1927. Crudup smiles and walks down the driveway, extending his hand. Broad, muscled and strong, the color of earth, it is a hand that's no stranger to hard work.

It's also a hand that could execute a perfect portacaval shunt in just under 13 minutes.

Crudup's father, Jonas, cut and delivered wood for a living and worked so hard that Crudup has few memories of him sitting down. His mother, Tommie, was the local midwife who would be called away at any hour of the day or night, then come home to tell her six children about the new life she'd helped bring into the world. The Crudup clan was well-known in Forest. Crudup's cousin, Arthur "Big Boy" Crudup - who penned Elvis Presley's first hit, "That's Alright Mama" - lived nearby.

While in high school during World War II, Crudup was drafted into the Army. He made it as far as Seattle, when a severe, persistent bout of food poisoning led to an honorable discharge. He returned to Forest to finish high school and marry Juanita Glover, his childhood sweetheart from just up the road.

But the deep South was no place for a bright, motivated young black man in the late 1940s. He could farm, perhaps, or get a job surveying land. Crudup wanted to go to college but had no money. And there was another barrier.

"I stuttered," recalls Crudup. "I stuttered so badly, people made fun of me. That's why I didn't go to college. I told my brother I would just find me a job and go to work."

Magic hands and a wake up call

He had a job at the poultry plant, worked at the lumber mill, and - always good with his hands - thought about being a mechanic. One day while unloading heavy bags of chicken feed from a train car, his own truck backed up suddenly and nearly killed him. It was a wake-up call; there had to be something better in the world for Jimmy Crudup.

Soon after, he followed several of his siblings north, first to Dayton, Ohio, then to Detroit.

By 1950, he and Juanita had settled in Inkster, Michigan, and Crudup went to work for the Clippert Brick Company driving an 18-wheeler. The couple soon had four children. Here the story could have wound to a predictable close: 40 years behind the wheel, yearly union picnics, a family to raise, church functions, retirement. Maybe a gold watch at the end of it all.

But it didn't work out that way. Instead, Jimmy Crudup, truck driver, crossed paths with C. Gardner Child, M.D., chief of the Department of Surgery at the U-M.

Child was an imposing figure. When he strode from Old Main Hospital headed for one of his labs, nurses would call ahead to alert everyone to look extra busy, to straighten ties and put on clean coats. Medical students and residents alike feared him and lived for his scant praise. In 1959, Child decided to turn a room in Medical Science I building into an animal research lab and set out to find just the right person to run that lab, care for the animals, keep the instruments clean and assist the surgeons who worked there.

Clippert Brick had gone out of business, and Crudup was looking for a job. His brother Jonas Crudup Jr. ran the morgue at the hospital and encouraged him to talk to Child. It was, Crudup recalls, not a particularly rigorous interview. Child hired him on the spot.

Watching and learning

Crudup spent the next six months setting up Child's new animal operating room, learning the names and uses of surgical instruments, practicing sterile technique, and assisting some of Michigan's top surgeons as they performed complex operations on animals. Crudup watched carefully.

On his own time, he spent hours studying anatomical textbooks, memorizing the placement and function of organs and the branching, flowing elegance that is the vascular system. Sometimes, when surgeries were completed and the subject animal had been euthanized, Crudup would perform his own exploratory surgeries, always looking to learn and understand more.

An animal lover, Crudup struggled to make peace with the fact that his new career involved working on animals - often dogs - and ultimately euthanizing them. "I used to tell my German shepherd, 'You don't know how lucky you are,' " he says. "The dogs we used were from the Humane Society - they used to gas unadopted dogs, but I felt these dogs should contribute something to science. They could make a surgeon better. They were never in any pain. We gave them pain meds just like you would give a human."

Before long, Crudup's vascular surgery animal lab was running smoothly. He learned to perfect heart, liver, and pancreas transplants. He implanted artificial veins and arteries, repaired intestines, inserted catheters to deliver drugs into livers and tested new techniques in plastic surgery.

A master teacher

Surgery residents spent their third year in research, and Crudup's job was to provide the animals for that research, as well as technical support. As he quickly found out, in most cases that meant actually teaching residents how to do the procedures necessary for their projects. Soon, word filtered out among the surgery residents, and down into the senior classes of the Medical School, about Crudup's extraordinary surgical skills, his laid-back demeanor and almost preternatural patience. He was, seemingly without trying, a master teacher.

"I worked with Jimmy as a senior medical student in 1975, and then as a resident from '78-'79," says Linda Graham (M.D. 1975, Residency 1981), vice chair for research and education at the Cleveland Clinic Department of Surgery.

"During my research year, I worked with Dr. Bill Burkel in cell biology and with Dr. (James) Stanley in vascular surgery, but for all the actual surgical procedures, it was just me and Jimmy and we worked together all day long, for many days. And you just establish an incredibly close bond."

That summer, under Crudup's close watch, Graham became a surgeon.

"He'd take me through the most complex cases with just a little grunt of approval and a little hesitation in his voice: 'OK you know, Linda,' he'd say, 'you really gotta think about this.' And as we worked, we would talk about life in general. He had such a wonderful outlook, a way of dealing with adversity. Growing up in the South wasn't an easy life, but he had a sense of inner strength and calm that was very helpful to me."

As one of few women in the Department of Surgery, Graham dealt with adversity of her own: an environment sometimes hostile to her presence. Crudup was supportive.

"Jimmy told me, 'You know, most of these men, they've never done much with their hands. Women have done more - stitching and sewing and the like. They can be good surgeons.'"

Neatly spread out on Crudup's dining table are the many academic papers he contributed to, in which he is prominently credited alongside the M.D.s and Ph.D.s. - studies of the endothelialization of Dacron grafts, of pancreas transplants and of post-surgical infection.

One is titled "Kidney Transplantation in Inbred Rats." On the cover is written, "To my good friend and teacher." It's signed, "Sherman."

Today, Sherman Silber (M.D. 1966, Residency 1973) is a world-renowned urologist, reproductive specialist and author who lives and works in St. Louis, Missouri. But when he first walked into Crudup's lab, he was a young urology resident with a confidence problem. "I always wanted to be a surgeon but was concerned about manual skill," says Silber. "I was a bookworm as a kid and had never done much with my hands."

"A mythical figure"

Silber had heard of Crudup during medical school - a "mythical figure" who was widely and openly regarded as the best surgeon at the U-M. "I thought I was going to meet this seven-foot-five-inch guy, but here was this mild, soft-spoken man. I asked him, 'Do you think you can make me into a decent surgeon?' And he just smiled and said, 'I think I can!' "

The two became a team, often working late into the night. Silber's skills and confidence improved and, together, they prepared to launch his research project.

The human kidney is about the size of a computer mouse; a rat kidney is about the size of a kidney bean. Microsurgery was in its infancy, and there were few if any instruments available to work on anatomical structures so small. Crudup simply fashioned some magnifying glasses, ground down the tips of some mosquito hemostats with a file, and started to explore kidney transplantation on rats.

"I had a few ideas for research I wanted to achieve," says Silber. "One was to study kidney transplants in animals so inbred that they wouldn't reject them."

"I just worked there..."

"No one had been able to do it," Crudup recalls. "Dr. (John E.) Niederhuber had been trying but could never get it perfected. That's when Dr. (Minor "Jud") Coon told me to try it. I wasn't the aggressive type, and I didn't want to be the first to do something. I wasn't a doctor; I just worked there.

"The arteries and veins in the kidney of a rat are smaller than the tip of this," he says, pointing to the pen that sticks out of his shirt pocket. "And you have to sew them together so the blood would flow through. I could do it with the glasses - I did the operation."

Word spread quickly; faculty and residents alike hurried over from Old Main to see for themselves. "That rat was just urinating all over the place!" Crudup laughs.

The operation became the basis for Silber's research project and the paper that followed. The two collaborated for several years, became good friends, and often thought creatively together about new surgical ideas. "The University did about 600 vasectomies a year," Crudup recalls. "I said to him, 'Well, now, if I can transplant a kidney from one 300-gram rat to another, why couldn't you reverse a vasectomy on a man?"

For Silber, it was the start of an unexpected career. "I never anticipated I'd develop a technique for vasectomy reversal, and that within 10 years I'd not even be doing regular urology. I run an infertility clinic and I love what I do."

When Crudup mentions a particular resident - and he does, frequently - his face twists into a suppressed smile that he won't explain. So the resident, Bruce Gewertz, M.D. (Residency 1977), does it for him.

Romantic advice

"I was one of the few single residents and I had girlfriend troubles at the time," he laughs. "Jimmy would provide the counseling. We had a great time with that."

Like so many others who studied with Crudup, Gewertz says that the lessons learned went far beyond surgical technique. "Jimmy did happen to be a great surgeon," says Gewertz, "but he was also firm and principled and value-driven - and very kind to people. Of course his background, being from rural Mississippi, was a challenge in the medical centers of the '50s and '60s. There weren't a lot of black faces with white coats. And yet Jimmy was uniformly respected."

James C. Stanley, M.D., the Marion and David Handleman Research Professor of Vascular Surgery and a director of the Cardiovascular Center, recalls that sometimes he and other senior faculty would be huddled together with Crudup, puzzling over a complex operation. "Jimmy would say, 'I was thinking' - it was like the TV commercial for E.F. Hutton, the investment company, whose advice mentioned by a golfer caused everyone in ear-shot to be quiet and listen."

Sometimes Crudup's strong values came up hard against the attitude of some of the residents. Gewertz recalls one young doctor who refused to consult Crudup as he operated on an animal. A lot of blood was lost.

"I could see from Jimmy's face and body language that this was offensive to him," says Gewertz. "He understood the importance of doing work on animals, but he respected the animals and didn't want them to be sacrificed inappropriately. That respect infused the lab with dignity." In 1984, Crudup won the U-M Jody C. Ungerleider Memorial Award for outstanding contributions toward the humane treatment of laboratory animals.

"Always something interesting"

If there's any injustice here - that circumstances of birth and geography and economics conspired to keep Crudup from a medical career of his own - he gives these thoughts no fuel. "I think that I could have been an outstanding surgeon," says Crudup, "but I don't worry about that. It wasn't meant to be; that's just the way things were. I enjoyed my work at the U. I never did dread going to work. It was always something interesting."

In a small office at the back of the house James Crudup built with his own hands, one wall is covered with awards, letters and newspaper articles honoring him. Seventeen years after he returned to Forest, word got out about his most interesting and unexpected career at the University of Michigan, rendering him a reluctant local celebrity. Out in the carport hangs a banner declaring that July 8, 2006, was "Dr. James 'Jimmy' Crudup Day" in Forest, Mississippi. Last May, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from Tougaloo University in Jackson. He was featured on NBC's "Today."

Stationed at a desk is the chair he was given by his Department of Surgery colleagues upon his retirement, but Crudup, like his father, doesn't sit down much (though Juanita, he says, sometimes sits there to watch the birds). Rather, Crudup spends his days helping his elderly neighbors.

"Plumbers 'round here charge you $65 or $70 an hour. Well, that's nothing but a little PVC pipe. If a door needs to be hung, or a window, or a roof needs fixing, I just go and do it.

"I can do 'most anything."

By Whitley Hill.

Reprinted with permission of Medicine at Michigan, Spring '08, Volume 10, Number 1.