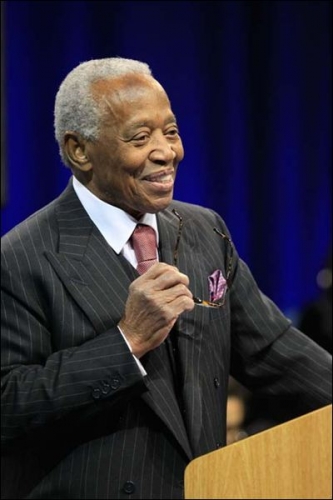

John W. Barfield

John W. Barfield, the son of an Alabama sharecropper, dropped out of high school, joined the Army, served for two years in Germany and France, and once discharged, went to work for the University of Michigan as a custodian. He cleaned toilets-lots of them. But his dreaming for a better life never stopped.

Even then, he was a visionary, driven to find a better way.

As a child, Johnny Barfield's parents, Lena and Edgar Barfield, lived in the "colored section" of a small town near Tuscaloosa, Alabama in a "shot gun" house as they were called. There was no indoor plumbing or electricity. Barfield lived there until he was five years old.

Whites lived in one part of town and blacks in another. They were "poor, not highly regarded" Barfield remembers. His father's work was dangerous, dirty work, in the fields, in the broiling Alabama sun.

Barfield knew early on he wanted to escape the grinding poverty that his father and mother endured.

Wanting a better life for his family, Edgar Barfield went "as a hobo" from Alabama to Pennsylvania, running alongside a railroad car and grabbing the ladder welded to the side of the car. He rode the rails 1700 miles, from Alabama to Washington, Pennsylvania, where he got a job in the coal mines, and when he had enough money, he sent for his family.

"If I had one last meal on this earth it would be beans and corn bread"

"Day after day I would see my dad come home from the mines," recalled Barfield. "He would get home, my mother would have three or four pots on the stove for his bath. The coal dust had an oil to it, so ordinary soap wouldn't remove it." Barfield can still imagine-almost taste-the pinto beans, cabbage, corn bread, fried pork his mother put on the table for dinner-a meal his father sometimes slept through. "If I had one last meal on this earth it would be beans and corn bread," he says.

"I knew by the grace of God that I was going to do something different," Barfield says. "I was nine, and delivering newspapers. [Delivering papers] took me into the better areas of town. One of his customers, who sold powdered soap, took the then young Johnny Barfield under his wing.

"I couldn't get enough of learning"

"He would sell [the soap] from house to house for fifteen cents a box. He wore a shirt and tie to work. He went to work clean and came home clean." Barfield asked him if he could help. "Well, Johnny," the man said, "Do you think you can do this?" "Yes," Barfield said eagerly. The man gave Barfield a job, sweeping the floor and loading the boxes. "I couldn't get enough of learning," Barfield recalled.

Within seven or eight months, Barfield could run the man's business as well as he did. "He saw something in me. I was an entrepreneur at 8 years old."

The crowning moment was when Barfield asked the man if he could try selling the soap. Once again, the man asked, "Do you think you can do this?" Barfield, once again, said yes. So Barfield got busy walking through the neighborhood, knocking on doors, with a heavy load of soap boxes on his back, selling boxes of soap. "Who's going to say no to a nine year old boy? They didn't buy one box, but five. Or six!"

Then the man gave Barfield a commission. "Five cents for every fifteen cent box sold," Barfield remembers.

"He had shown me the path I had been looking for. I was learning to be a businessman. I have been on that path ever since."

Good work washing walls in Angell Hall

When Barfield was 15, his family moved to Ypsilanti. At 17, he joined the army, dropped out of school. "I got out of the Army and the U-M were hiring window and wall washers. I applied and was hired. I washed the classroom walls in Angell Hall. It was good work. At the end of the wall washing season, the U-M offered me a job as a janitor in the Chemistry Building across from the Women's League." Barfield worked there from 1949 through 1954, and was paid $70 per week. That was fine, until he married and had a child. Then he needed to make more.

"I asked the profs if I could wash and wax their cars over the weekend With a fifteen cent investment (he figured out that corn starch gave a better shine and was quicker) I increased from 15 dollars to 20 dollars [a car] and from one car to six."

Lessons learned from work

Once again, he applied lessons learned from work to innovation and entrepreneurship.

He noticed a lot of new houses were being built in Ann Arbor, and the builders did not want to clean them. They didn't want to wash windows and floors. That was beneath them. They didn't want to scrub toilets. They wanted to be carpenters and plumbers. So Barfield asked the builders, "Why don't you let me clean these houses on a contract basis?"

"I showed them how I could clean better and that would reflect better on them. I would wash the windows, clean and disinfect the toilets, sweep, and I laid paper on the floor so that the movers didn't hurt the floors. They liked that."

Within two years, Barfield and his wife had the largest cleaning business in Ann Arbor. He left U-M in 1955 to start the Barfield Cleaning Company.

Word spread that Barfield did good work. Soon he was cleaning commercial businesses, and even started a janitorial cleaning school, which became a national model. In 1969, Barfield sold his cleaning business to International Telegraph and Telephone Company, one of the five corporations interested in buying it. He created and sold several other businesses after that, including Barfield Building Maintenance Company (bought by Unified Building Maintenance Services, Inc.) and Barfield Manufacturing Company (bought by Masco Tech Industries). In 1977 he incorporated as John Barfield & Associates, which later became the Bartech Group.

Giving back and paying forward

Barfield has honored his parents along the way by sustaining a good reputation, and giving back. He generously supported humanitarian causes, including feeding the hungry to building wells and providing safe drinking water in Haiti and Africa. His leadership style and generosity earned him many honors, including the Tree of Life Award, the Jewish National Fund's highest humanitarian honor, the George Romney Award, for his achievement in volunteerism, and the A.G. Gaston Award for his life-long commitment to the African American business community. He also proudly received two honorary doctorate degrees, from Grand Valley State University and Cleary College.

"It is more important to have a good name than to be rich," he says, repeating the lesson that his parents taught him. "If you're willing to pay the price and do everything that is honest and fair, you can be anything you want to be. The only person who can stop you is yourself."

In 2012, The Bartech Group, now run by one of Barfield's sons, celebrated its 35th anniversary. Now in his eighties, still happily married, with successful children of his own, John W. Barfield looks back on his life with no regrets. "The lessons I learned early from my parents sustained me," he says. "The more you do for others, the better you feel about yourself."

By Jan Schlain